The year 2017 is leaving behind its past 12 months, which were marked by global fluctuations. Amid the structural problems of Middle East and Far East-centered political crises that led to the pursuit of short-term political solutions and social reactions in some countries, we will evaluate the 2017 performance of the European economy.

The biggest change in the European economy was undoubtedly the decision by the European Central Bank (ECB) to take further expansionary steps in a market showing weaker global growth than in previous years. In particular, ECB President Mario Draghi and Vice President Vitör Constancio's promising statements given throughout 2017 were the preview of pioneering recovery efforts; however, systemic risks are still present.

The presence of deteriorating risks in terms of economic activities and inflation led the ECB to set a negative interest environment and an expanded asset purchase program. Steps taken against this environment partially balanced inflation concerns, but not enough to improve the deflationary spiral in Eurozone economies. Accordingly, the ECB preferred to maintain its expanding monetary policy and extend the asset purchase program throughout the year 2017 so that the wheels of the economy would continue to turn.

Specifically, the ongoing state of "arm wrestling" and protective policies between the United States and the European Union led to serious reactions in the EU block's increasing economic integration. In particular, the middle class among developed EU members started to believe that economic integration was beneficial to other member states but not to themselves, while protectionist speeches became more and more common in the European Parliament after the Brexit vote.

The almost 9-year-old economic crisis in Greece continues to hamper Germany's effort to keep the union alive. Partial improvements in countries like Spain, Portugal and Ireland, which still suffer from the effects of the mortgage crisis, are one of the most important reasons the economy continues to develop.

The big question in the minds of renowned European economists is why the Eurozone was not able to revive its inflation and growth despite all the extraordinary monetary policies adopted by the ECB.

Before answering this question, one should look at the ongoing risks of 2017. In Italy, which is, together with Germany, one of the most important machinery and heavy industry manufacturers in Europe, the rate of receivables followed-up by banks reached 30 percent. The amount of credits Italian banks are not able to refund, also known as problematic credits, have reached approximately 360 billion euros.

According to official figures, companies and individuals responsible for around 200 billion euros of these problematic credits have already gone bankrupt. With increasing concerns of investors in the banking system, Italian banks lost about 50 percent of value from the beginning of 2017. In short, if the ECB continues to track the issue from a distance, the Rome-based financial crisis may spread to Brussels and Frankfurt. If we consider that Italian banks are responsible for two-thirds of the problematic credits in the Eurozone, which is made up of 19 members, the severity of the crisis becomes more obvious. Expecting Italians or Spaniards, who stopped believing in their own financial systems, to turn toward consumerism or perform long-lasting investments would be a mistake for the EU. Unless the low interest loan atmosphere adopted by the EU to revive internal consumption is supported by structural reforms, a positive resolution for these two countries seems impossible.

The only common ground for the EU is that the Brexit process with the United Kingdom has been a real difficulty. The U.K., which began receiving increased migration from Eastern and Southern Europe due to the high rate of unemployment and regional wage difference and supported the economic loads of countries such as Romania, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, the Czech Republic and even Greece, has been questioning the Union under the dominance of Germany and France for the past 15 years.

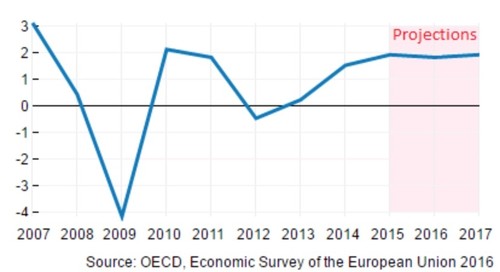

A chart showing real GDP growth in Europe, % change from the previous year

The fact that nearly 24 billion sterling was recorded as a deficit for the U.K. as part of its EU trade at the end of 2016 was the last straw. Ultimately, the U.K. decided to set the yearly EU budget on the island at 8 billion pounds and to quit the Union, which led to the current unsolvable problem. In particular, issues like the payback and compensation required by Germany from the U.K. over the past months in addition to the state of EU citizens living in the U.K., Northern Ireland's future status and the border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic continue to be problematic.

No one knows how long the Eurozone can bear these problems with Germany's exports, France's market diversification and Eastern Europe's low labor costs. The Eurozone and the EU, which have reflected positive market growth, while at the same time inefficient productivity, grew 0.6 percent in the third quarter of 2017 compared to the second quarter. According to Eurostat, the seasonally adjusted gross domestic product (GDP) of the Eurozone increased by 2.6 percent.

In the third quarter of 2017, household consumption expenditures and gross fixed capital formation had positive effects on both the EU and the Eurozone, while the trade balance had some positive impact on GDP growth. During this term, household consumption expenditures increased by 0.3 percent and 0.5 percent in the EU and the Eurozone, respectively.

Third quarter GDP increased most in Romania with 2.6 percent, followed by Malta with 1.9 percent, Latvia with 1.5 percent and Poland with 1.2 percent. In Denmark, the GDP decreased by 0.6 percent during the same period.

The increase in the GDP was 0.8 percent in Germany, 0.4 percent in Italy, 0.5 percent in France, 0.8 percent in Spain, 0.4 percent in the Netherlands, 0.4 percent in the United Kingdom and 0.3 percent in Greece.

So what do these figures show us? This is the answer to the above-mentioned question on why the Eurozone is able to revive its inflation and growth despite all the extraordinary monetary policies adopted by the ECB.

As was observed throughout 2017 around the world, the biggest pressure on inflation was posed by low oil prices. To public knowledge, the ECB's first aim is to obtain an inflation rate of 2 percent. Although the expansion of the private sector, which is the Eurozone's life-blood, showed some recovery, the service sector continued its weak progress throughout 2017.

The slowdown in the service sector is especially important as it may put pressure on economic expansion in 2018. Nonetheless, the manufacturing sector saw moderate expansion in the last quarter of 2017.

Additionally, the fact that nationalist and radical parties have gained ground in European politics underlines the importance of protecting the unity of the European Union. If we consider that U.S. President Donald Trump's biggest two rivals in achieving his American dream are China and the Eurozone, to speak about double-digit expansion figures for 2018 and the following years would be no more than a dream. The two technical issues needed for the euro to gain dominance against the U.S. dollar would be for the EU to abandon its monetary expansion and the Federal Reserve Bank (Fed) to abandon increasing interest rates.

I believe that monetary expansion is a necessity for Europe's monetary expansion, which is why the first scenario is inconsistent in its entirety. As the Fed increases its global action, it is currently impossible to forecast its next moves. With increasing unemployment rates in the Eurozone, it would be suicide for the EU to adopt austerity measures.

As a result, in 2017 the EU generally saw a passing grade; however, with the unemployment rate sticking at 20 percent, the nationalist movement in Catalonia energizing other minorities in the EU and the opportunities awaiting the U.S. show a gray future awaiting the EU in 2018.

* Ahmet Akyıldız / Ph.D. researcher in Private Company Economic Research Department MENA at Swiss Business School