On a rainy winter day in Istanbul, it is not normal to see long lines of people waiting to buy vegetables at mobile sale points. Usually either neighborhood retail marketplaces or grocery store chains are the universal addresses for food shopping in Turkish cities. What has prompted the citizens in Turkey's most-populated metropolis to go out and wait in line just to buy vegetables? The answer to that question is affordable prices for fresh produce.

Though the public agenda of the past was preoccupied with this issue, but it has been dormant for years. The municipalities in the country's two largest cities, Istanbul and Ankara, established sale points that sell a number of agricultural products to average consumers at prices way lower than those at neighborhood retail marketplaces or supermarket chains.

This practice "tanzim satış" – "tanzim" means order, regulation and regulating in Turkish and "satış" mean sale – is not something alien to the Turkish public. The history of this practice dates back to the 1970s, during which the global economy experienced a crisis. It recently emerged again when the government decided to intervene in soaring consumer prices on foodstuff.

The Turkish economy has been tackling high inflation for the last year. Consumer prices peaked in October and hit 25.24 percent. A series of fiscal measures, slowing demand and the tight monetary policy, ensured downward movement in inflation in November and December, lowering it to 21.62 percent and 20.3 percent, respectively.

Although the inflationary pressure has started to signal improved outlooks, food-price inflation continued to rise in January, recorded at 30.97 percent. The stubborn surge in food prices has been primarily explained by seasonal conditions that do not allow for the optimum heat and environment for the growth of crops and harsh weather conditions that struck the greenhouses and fields near the Aegean and in southeast regions. This account, however, was not welcomed as satisfactory for the prices that troubled the public and government officials.

In the eyes of ordinary citizens and government officials, there is one other element to hold accountable: the profit-seeking middlemen who are responsible for the transport and delivery of agricultural produce. They are dubbed "profiteers" and "opportunists" since they increased the commissions they charge at every turn of food delivery operations, from the transfer of goods to the cold chain and their sale to market sellers and supermarkets.

In brief, increasing fuel and fertilizer costs – raised by the tumbling Turkish lira for the last four months – decreased production, the rising number and intensity of natural disasters and the lack of action to regulate the market are often cited as the main causes of high food prices.

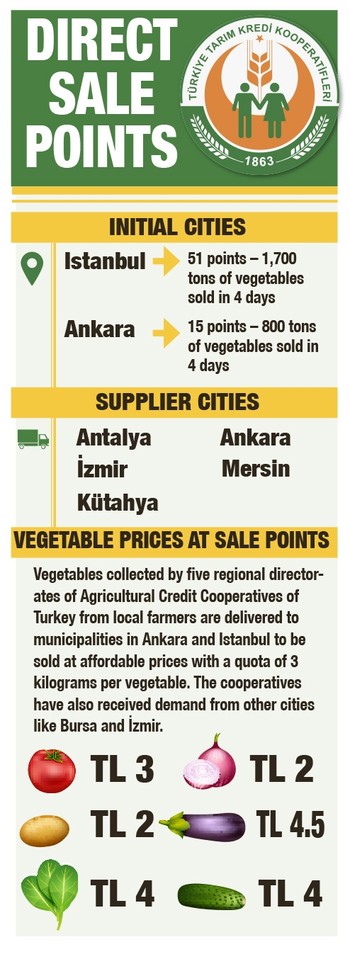

Urged to take action and intervene in this process to relieve citizens of the burden, the government decided last week to establish stalls run by metropolitan municipalities in Istanbul and Ankara and sell vegetables at reasonable prices to average consumers. The practice was initially launched at 51 direct sale points in Istanbul's 34 districts and at 15 direct sale points in the capital province Ankara. Opening at 10 a.m. and closing at 7 p.m., the municipal direct sale points have so far experienced a high demand from citizens.

With the aim of uncovering citizens' reactions to the direct sale points, the Daily Sabah Economy team embarked on a journey in Istanbul on a rainy Wednesday morning and talked to citizens who lined up to buy the products offered at direct sale points.

"This is a belated practice. The officials should have started long ago. The profiteers should learn their lessons," Ferit, a 57 year-old pensioner, said while waiting in the line to buy tomatoes and other agricultural produce, which Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality bought from the Agricultural Credit Cooperatives of Turkey.

"We want the direct sale points to be permanent. Our state is powerful enough to regulate this. We also demand a wider product range. I think the sale points should also offer dairy products and meat," Ferit added and continued, "The government should inspect all aspects of food distribution and delivery process."

"This is my first time here. We are happy to buy vegetables at lower prices, and we want this practice to be continuous. It would be better if more products are added," Sevim, a 65-year-old female pensioner, told Daily Sabah. Sevim explained that only a couple of days ago she paid TL 10 for a kilogram of spinach, complaining of high prices. A kilogram of spinach is sold for TL 4 at municipal direct sale points.

"If the state wants, the problem of high prices can be solved with a regulation for the wholesale marketplaces. This solution should be permanent," said Mustafa. He stressed that he is waiting in line to support the government's war on food terrorism, as he believes the prices have been inflated by opportunists in wholesale markets.

İbrahim, another pensioner residing in Çapa neighborhood in the historical district of Fatih in Istanbul, recounted a childhood story. When he was living in Büyükçekçe district in 1955, a local shopkeeper who used to sell vegetables and fruits would market his cucumbers as fresh and lower prices from which he only secured a 50-percent profit. "Later, when the municipal police came and investigated, they found that this local shop owner was selling his cucumbers at unreasonably high prices as he doubled the profits," İbrahim said. This shop owner later served a three-month sentence, he added.

İbrahim told this story while waiting in line to emphasize his argument that the relevant government authorities should inspect every step of food distribution, particularly middlemen and distributors, in a more tight and disciplined fashion. "The sellers in the neighborhood marketplaces pay TL 0.70 for 1 kilogram of oranges, but they sell it to average people for TL 2.50," İbrahim argued, echoing a very popular argument among citizens.

Halil, a middle-age fellow, stressed that the direct sale points are not a permanent solution, and the authorities should introduce a more stable solution to alleviate citizens of the burden of food prices. "But this solution will be a lesson for the distributors at wholesale marketplaces. They should be made aware of their wrongdoings," he said. The government has aired the dirty laundry of these profit seekers in public, he argued. "As citizens, we are demanding a regulated people's market in each district," Halil noted.

A female official from the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality overseeing the sales procedure in Aksaray told Daily Sabah that she had received positive comments from the citizens. "After the amount of vegetables diminishes with sales, we call the municipal center and they send more products in trucks," she said, emphasizing the continuous flow of stock at the sale points.

Other than local citizens, tourists as well were waiting in line to buy affordable vegetables from a sale point in Taksim Square, in the heart of Istanbul.

"I don't know a lot of Turkish," Leyla from Kazan, the capital city of the Russian region of Tatarstan, said, while waiting in line at the Taksim direct sale point. Leyla and her four friends were on a 10-day vacation in Turkey. "We went to the public markets and other supermarket chains, but the prices are high. One of our friends told us about this sale point in the square," she said. Leyla said she and her friends were very surprised that the price of pomegranates was TL 2.50, while the price of tomatoes and onions per kilogram was around TL 7, adding it was the other way around in their country. Since they have been visiting Turkey for almost 15 years, she said they are familiar with the prices, as they love to cook for themselves during their stay. "We are pleased with the practice. We would be even happier if fruit was also sold at these kinds of points," Leyla said.

"Prices are really moderate compared to markets and greengrocers," said Mehmet, who works at an insurance agency and lives in Cihangir, located just around the corner from Taksim Square. "Potato prices in nearby markets stand at TL 4.50, the cheapest tomato price is TL 6, which makes prices here a lot more moderate," he said.

When asked whether he would like this practice to become permanent, he said: "Of course it would be good, why not? There were neighborhood retail marketplaces in Ankara when I was a child. Everyone was buying produce from there. It was pretty good," he noted.

"I do not shop in supermarket chains. I do not prefer them. Since I was raised in a neighborhood culture, our local grocer is there, our greengrocer, our butcher... We always buy from them. I side with neighborhood culture," he said. He also remarked that a compromise should be found so that shopkeepers are not negatively affected. "We want these sale points to be permanent, but not in this way. They can be turned into stores or a public market," said two people, who preferred to remain anonymous given their official posts, while waiting in the line.

"The municipality doing such things gives confidence to the citizens. We think we are buying healthier, quality products," one of them said. They referred to a series of natural disasters that hit the Mediterranean province of Antalya, where Turkey's greenhouse agriculture and investments are largely focused, high oil fuel prices and increases in the exchange rates as the main reasons behind the recent hikes in the food prices.

At the direct sale points, there is a purchase limit of 3 kilograms per item, as they aim to reach as many people as possible. The two people agreed that the purchase limit should be lifted.

Produce at direct sale points supplied by agricultural cooperatives

The vegetables sold at municipal direct sale points are supplied from five regional directorates of the Agricultural Credit Cooperatives of Turkey, including Antalya, İzmir, Kütahya, Mersin and Ankara, the spokesperson for the cooperative's general directorate said on the phone.

"The agricultural credit cooperatives collect the produce from its partners in the five regions, namely farmers and producers," he said. "In the four days the practice was in place, from Monday to Thursday, the cooperatives sold a total of 1,700 tons of vegetables in Istanbul and 800 tons in Ankara," the spokesperson added.

Antalya Regional Directorate Head of Agricultural Credit Cooperatives of Turkey Yakup Kasal told Daily Sabah that Antalya alone supplied 1,400 tons of vegetables in four days to meet the demands from Istanbul and Ankara metropolitan municipalities. "We have already received demands from Bursa and we are now working to organize the supply of vegetables for Bursa," he said.

"If municipalities or supermarket chains request vegetables supplies from us for 365 days a year, we are capable of responding to that demand. It should not be a problem that agricultural credit cooperatives account for 15 to 20 percent of the whole food trade in Turkey," Kasal remarked and noted that a truck that sets off in Antalya reaches Istanbul in only nine hours.

When asked how they managed to keep prices affordable for ordinary consumers, he said: "We do not add any commission fees. We buy a kilogram of potatoes for TL 2.50 from producers, and we only reflect the transfer and insurance fee." Kasa

l stressed that they have planned the supply process very carefully to not burden producers and consumers. "When we heard the news, we came together with our producers and officials from the ministry. All parties made the necessary calculations and we decided to buy the vegetables from producers for marketplace prices to protect the producers," he explained. The produce, he added, is packaged and loaded on trucks after the final approval of agricultural engineers in order to emphasize that every step is implemented carefully.

The prices at municipal direct sales points are significantly lower than the country's average in January calculated by the Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat). One kilogram of onions sold for TL 2, compared to the January average of TL 4.90. For tomatoes, 1 kilogram is sold for TL 3, half of the average price of TL 6. In comparison, 1 kilogram of potatoes costs TL 2, compared to TL 3.60 of the January average. Moreover, consumers pay TL 4.50 per kilogram of eggplant and TL 4 for 1 kilogram of cucumbers.

State-run postal service starts selling vegetables online

The state-run postal service Turkish Post and Telegraph Organization (PTT)'s online marketplace platform www.epttavm.com started selling "tanzim" vegetables on Thursday, following Transportation and Infrastructure Minister Cahit Turhan's announcement earlier this week.

Fruit and vegetables on www.epttavm.com are now available at prices set by the direct sales points, and all products will be delivered safely to people via PTT Cargo and Logistics. The website, Turkey's national online marketplace, has assumed the responsibility so that people do not have to wait in line and can buy cheap vegetables and fruit in favorable conditions.

According to a statement released by the PTT, eight different vegetables – peppers, potatoes, onions, tomatoes, red peppers, banana peppers, cucumbers and eggplant – are being sold on the online platform in the initial phase. The practice will later be offered in other cities apart from Ankara and Istanbul. The purchase limit at 3 kilograms per product is also valid for the PTT platform. The orders are delivered the next day, the statement added.