It was a characteristic winter evening in Istanbul as gray skies hovered south from the Black Sea to obscure a rare bout of sunlight in the cold season. The humid air of mid-February thickened between its two seas, the inlet and the strait. A wind chill crept over the steep, urbanized valley forests from the Bosporus shores. On the high ground of Tepebaşı, a core district in the city named for its location on the top of a hill overlooking the Golden Horn, the Art On Istanbul gallery opened its elegantly-arched glass door to welcome loyal collectors, collegial curators and fellow artists for the opening of the first solo show by Ahmet Çerkez.

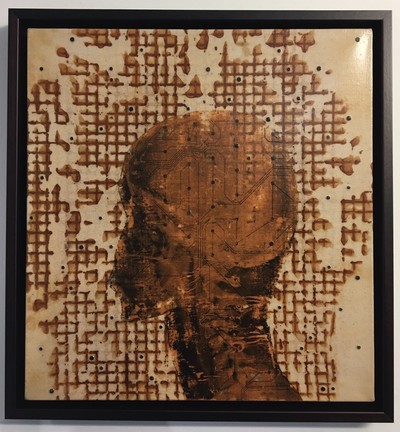

A buyer walked in and immediately seized "Untitled" (2018) -- in fact, all of his pieces are untitled -- a well-composed rust, acrylic and collage on canvas that Çerkez had fashioned sometime within the brief month and a half before the exhibition opened. Its diagrammatic circulation of meshed and haloed patterns distills the central theme of the exhibition, "Stateless Maps" with characteristic subtlety and precise technique.

Over his recurring skull motifs, Çerkez implants an urbanized aesthetic through his rust-infused canvases.

For the last two years, Çerkez had prepared the pieces that now appear at Art On Istanbul with distinction from his earlier works as they are crafted with a piercing cartographer's eye as one ruled by a sense of linear direction across conceptual space. His works follow a particular color scheme uniformly based on the cinnamon red of wet rust. It is an aesthetic of urbanization, recalling the pavement-stained oil spill art that Tom Waits designed for the cover of the Winter 2005 edition of Zoetrope All-Story, the award-winning literary magazine published by The Godfather director Francis Ford Coppola.

Art On Istanbul printed textual commentary on the show by Can Özbaşaran, a careful thinker who delved into the likes of John Berger and Katharine Harman's book "The Map as Art: Contemporary Artists Explore Cartography" to expound on the exhibition. His insightful words are an intimate look into the inner life of Çerkez as a young artist first exploring himself. After the translation from Turkish by Öykü Özer, he writes, "Çerkez weaves together his story, which he begins to relate using rational lines in a rather unplanned manner, with pieces of his personal experience of immigration at early ages." As a young boy in the 1980s, Çerkez and his family of Balkan Turks left Bulgaria, where they had settled in the Ottoman era. They made the epochal return to Turkey as multigenerational returnees, one of many waves of global migration that followed the rise of modern national borders.

Çerkez is a cartographer of otherworldly geographies as he charts the path within while paying homage to his family who emigrated from Bulgaria to Turkey.

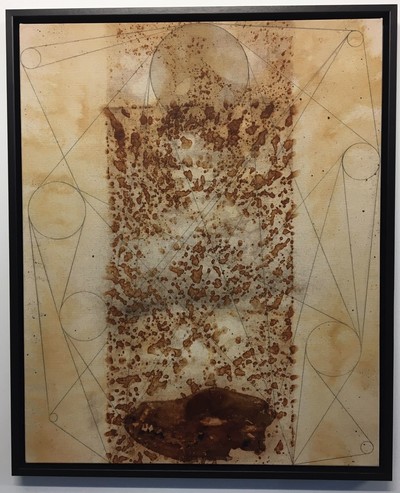

That shared reality is one that Çerkez captures with animating power, as he reconstructs the ingredients of overland journey with materials that give a sense of passing time. Rust, for example, is his staple component, shot through the entire oeuvre of the show, often collaged together with fallen flower petals. In a pair of graphically similar pieces, he evokes the photographic symbol of a solar eclipse, an auspicious metaphor of cyclical time, often marking the memory of a people, also signaling the anticipation of the future. Many of his works picture organic matter as they appear through the foreground as in the hallucination of a metaphor.

A transparent skull is gridded and splotched with blood-red dyes, almost buried under vegetal shapes while the past is lost to the traumas of forced exile. In another, a black scorpion floats above patterned abstractions, dotted and rounded like the monotonous forms of a settlement, one abandoned by the looming threat of certain death. One in this vein that could be interpreted for its relative optimism is of a plucked leaf, decorated with reverent motifs, which hangs detached, free of twig and branch, tree and root, falling over a pile of flower petals.

The Republic of Turkey, as much as it is an idea of grandeur, is an entity in the world fixed by the pragmatics of reality. Like all things, it exists in relation to its opposite. In that way, modern nations-states are dichotomized by stateless peoples, regardless of political confrontation. The stateless live within official borders and in diaspora. In the authoritative language of international law, migrants and separatists typically encompass alternative narratives beyond that which a nation recognizes as its own to be taught in schools, fostered in youth and advanced by the people. Yet, there are others. Individually, and informally, artists often speak on behalf of the more marginal of human experiences, those that transcend the normative bounds and rules and conformities of any ideology. The artist is an activist of the soul.

Çerkez represents that classic crossover where historical migrant identity and creative impetus in art are integrated into forms of expression that are free from the dogmas and impositions of the masses. And yet, the artist of migratory subjects, such as is rendered through figurative abstraction in "Stateless Maps" also represents the human weakness of simply being lost, vulnerable, flung into the unknown where the very earth is unrecognizable. Many questions arise when looking at his canvases. Are these interpretive maps that he has drawn to better understand the new and strange land into which his ancestors immigrated? Is he charting a path within to an otherworldly interior beyond nation-states, even beyond states of mind?

One of his exhibited works particularly conjures the appearance of old, vintage maps from the Age of Exploration in the three centuries following the earliest American colonizations. Its concentric circles are deftly placed to accent the effect of seeing worlds within worlds, drawing from endless cartographies where boundaries overlap and dissolve like his persistent use of corroding metal to signify the impermanence and statelessness of the most enduring of all that is manmade, from construction materials to the ideal of unity. His geometrical outlines detail inhuman visions in which skeletal x-rays and encapsulated cities are shot through with the connecting dots of microchip infrastructures and microcosmic gridlock.

And yet there is a poetic beauty about the whole of his intensive focus. He is a cartographer spinning globes and sweeping dust from waterlogged and molding tomes of faded drawings and broken texts from the furthest reaches of the world, attempting to lodge it all back into his all-too-human mind through study and invention. The art of Çerkez is a wise reminder to all who despair in confrontation with the deceivingly permanent, utterly temporary walls and dams of modern, industrial nationalism.

For one of his larger pieces, he borders a rusty collage of intersecting rectangles with a poem by Emily Dickinson, the antisocial recluse whose verse stands the tests of time and crosses cultures. Özbaşaran quoted the Argentinean poet Juan Gelman, "again we're going to begin all of us / against the great defeat of the world" to capture the underlying sense that identity is malleable, amalgamating with others and dissolving internally like the natural phenomena that often lives and dies unseen where the liminal and stateless coexist on the remote borderlands and in the sprawling heart of the citified modern nation.